Task II.H: Night Operations

Lesson Overview

- Objective

-

The student should develop knowledge of the elements related to night operations and understand the unique factors that are inherent to night flight.

- Reference

-

-

PHAK

-

AFH

-

AIM

-

- Key Elements

-

-

Off-center viewing

-

Instrument indications

-

Maintaining orientation

-

- Elements

-

-

How the eyes work

-

Disorientation and night optical illusions

-

Pilot equipment

-

Preflight

-

Engine starting

-

Taxiing, airport orientation, and the runup

-

Takeoff and climb

-

In-flight orientation

-

Traffic patterns

-

Go-arounds

-

Night emergencies

-

- Equipment

-

-

White board

-

Markers

-

References

-

- Schedule

-

-

Discuss objectives

-

Review material

-

Development

-

Conclusion

-

- Instructor Actions

-

-

Discuss lesson objectives

-

Present lecture

-

Questions

-

Homework

-

- Student Actions

-

-

Participate in discussion

-

Take notes

-

- Completion Standards

-

The student understands the factors involved in night operations and can confidently and safely pilot an aircraft at night.

Instructor Notes

- Attention

-

A lot of people prefer night flying to day fling. The air tends to smoother, the radios tend to be quieter, there’s less traffic and it’s more relaxing.

- Overview

-

Review Objectives and Elements/Key ideas

- What

-

Night operations are the factors dealing with and the operation of the airplane at night.

- Why

-

It is important to talk about night flight as it presents many unique situations which, if ignored, can result in dangerous situations. Also, if you learn to use your eyes correctly and know your limitations, night vision can be used more effectively.

How the eyes work

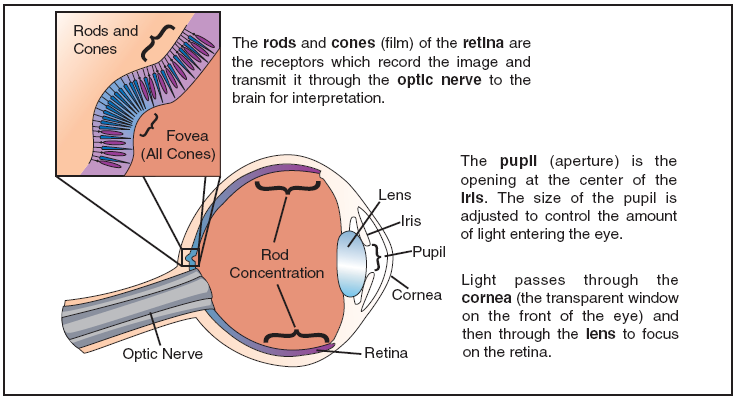

Rods and cones

Rods & Cones are the two types of light sensitive nerve endings which transmit messages to the brain via the optic nerve.

- Cones

-

-

Located in the center of the retina, the layer upon which all images are focused. Responsible for color, detail, and far away objects.

-

- Rods

-

-

Located in a ring around the cones, function when something is seen in the peripherals and provide vision in dim light. Make night vision possible.

-

- Fovea

-

-

Small pit where almost all the light sensing cells are cones.

-

The area where most looking occurs.

-

Both rods and cones are used for vision during the day. Without normal light, night vision is placed almost entirely on the rods. * Day - can see objects by looking at them directly. * Night - off-center viewing is more effective. Middle field of vision is not very sensitive, creating a "night blind spot." Rods are more numerous farther from the fovea and are used to see in dim light. Almost all of Night vision is based on rods.

Large amount of light overwhelms rods—they take a long time to reset and adapt to the dark again (~30 minutes to fully adapt). Once adapted, rods are ~100,000x more sensitive to light. Process reverses when exposed to light—eyes adjust to light in a matter of seconds. Avoid bright lights before and during a flight, so use minimum brightness of cockpit lighting that will allow reading of the instruments/switches without hindering outside vision

Disorientation and night optical illusions

Along with general low light limitations, there area a number of illusions which are specific to night operations.

- Autokinesis

-

Autokinesis an illusion where staring at a single point of light can make it seem to move. This can cause the pilot to mis-identify the light as a target, and can be prevented by changing the focus of the eyes and avoiding fixation.

- False Horizon

-

This is caused when the natural horizon is obscured at night, and can be generated by confusion between bright stars and lights on the ground. Trust your instruments.

- Featureless Terrain

-

This is an absence of ground features which can create the illusion that the aircraft is higher than it really is. This can result in a lower than normal approach. Trust your instruments.

- Runway Slopes

-

An up-sloping runway (or terrain) can create the illusion that the aircraft is higher than it actually is, thus potentially flying a lower approach. For a down-sloping runway (or terrain) the opposite is true. Be prepared by using the chart supplement to know the slope that will be encountered.

- Ground Lighting

-

Regularly spaced lights, such as along a highway, can create the illusion that it is a runway. Moving trains have also been mistaken for runway/approach lights as well. Overly bright runway lights can create the illusions that the aircraft is closer than it really is, and maintaining situational awareness is the key way to mitigate these illusions. Know what to expect, and use tools such as navaids to maintain that situational awareness.

Reference to flight instruments and knowing what to expect at the destination are key tools to avoid succumbing to illusions. Tools such as using an ILS or a VASI at night to insure correct vertical guidance can be useful. At night incorporate instruments into the scan more heavily. If there is ever any doubt, go around.

Verify attitude by reference to flight instruments

The best way to cope with disorientation and optical illusions is by reference to flight instruments. If making an approach and an ILS or VASI is available, make use of it. Visual references are limited—you will need to use more instruments, but don’t be dependent on them. If at any point you become unsure of your position, execute a go-around.

Pilot equipment

- Flashlight

-

-

White light is used to preflight the aircraft;

-

red light is used when performing cockpit operations, as it will not impair night vision as much.

-

When using a red light on an aeronautical chart, the red colors will wash out.

-

-

- Aeronautical charts

-

if the intended course of flight is near the edge of a chart, keep the adjacent charts available. City lights can be seen at far distances, and charts are helpful at clearing out confusion.

Organization eases the pilot’s burden!

Preflight inspection

Required equipment for VFR flight at night

TOMATO FFLAMES and FLAPS

-

Fuses

-

Landing light

-

Anti-collision lights

-

Position lights

-

Source of power

IFR-required equipment does not hurt

Preflight inspection is still necessary. Use a white light flashlight, andcheck all aircraft lights. Don’t Forget! Check the ramp for obstructions. Obstructions on the ramp might be harder to catch from the flight deck at night.

Engine starting

Be sure the propeller area is clear. Turn on position and anti-collision lights prior to start, and announce “Clear prop.”

Keep all unnecessary electrical equipment off to avoid draining the battery.

Taxiing, airport orientation, runup

Reduce taxi speeds because of restricted vision. Do not taxi faster than a speed that will allow you to stop within the distance you can clearly see.

-

Use the landing/taxi lights as necessary—caution overheating (no airflow).

-

Do not use strobes/landing lights in the vicinity of other aircraft, as they can be distracting or blinding.

-

Use an airport diagram, and understand taxiway markings, lights, and signs.

-

Perform the before taxi runup with the checklist, as usual. Forward movement of the airplane may not be easy to detect. Hold the brakes and be alert that the airplane could potentially creep forward without being noticed.

Takeoff and climb

Clear the area for approaching traffic on the final approach. At non-towered airports, make a 360° turn in the direction of air traffic, to clear the area.

-

After receiving clearance, align the airplane with the centerline, and check to ensure the magnetic compass and directional gyro match the intended runway.

-

Perform a normal takeoff, depending more on instruments, as many visual cues are not available. Perception of runway width, airplane speed, and flight attitude will vary at night.

-

Check flight instruments frequently.

-

Adjust pitch attitude to establish a normal climb as the airspeed reaches VR.

-

Refer to outside visual references (e.g. lights) and flight instruments.

-

Check attitude indicator, vertical speed indicator, and altimeter, to ensure the airplane is climbing. The darkness makes it hard to tell by outside references.

-

Make necessary adjustments by referencing the attitude and heading indicators. Don’t make any turns until reaching a safe maneuvering altitude.

In-flight orientation

-

Checkpoints—there are less of them, but it does not pose a problem.

-

Light patterns of towns are easily identified. Rotating beacons are useful. Highways make good checkpoints. Easier to become disoriented in relation to location—continuously monitor position, time estimates, and fuel consumed.

-

Use NAVAIDS whenever possible.

-

Difficult to see clouds at night—exercise caution to avoid flying into MVFR/IFR weather conditions. The first indication will be the gradual disappearance of the ground and glowing around lights.

-

Use nav lights to orient other aircraft’s direction in relation to your own. Red light on left wing, green light on right wing, white light on tail.

Traffic Patterns

-

Identify the runway/airport lights as soon as possible.

-

It may be difficult to find the airport or the runways—fly towards the beacon until you identify runway lights, and compare the runway lights with your heading to ensure you are at the right place.

-

Distance may be deceptive at night due to limited light conditions — lack of references on ground and inability to compare their location and size.

-

Depend more on instruments, particularly the airspeed indicator and altimeter.

-

Use the landing light for collision avoidance, and fly a normal traffic pattern.

-

Know the location of the runway/approach threshold lights at all times.

-

When entering the pattern, allow for plenty of time to complete the before landing checklist, and execute the approach in the same manner as during the day.

Approach and landing

Make a stabilized approach, in the same manner as during the day. Use flight instruments more often, especially altimeter/airspeed indicator, as distance may be deceptive. Maintain specified airspeeds on each leg, and watch the VSI to keep the approach under control.

If there are no centerline lights, align the airplane between the edge lights. Note and correct any wind drift, and use power and pitch corrections to maintain a stabilized approach. If available, use approach lights (VASI, PAPI, etc.) to maintain glideslope.

Make a smooth and controlled roundout and touchdown in the same manner as in day. Impaired judgment of height, speed, and sink rate may create a tendency to round out too high. Start the roundout when the landing light reflects on the tire marks on the runway, or when the runway lights at the far end appear to be rising higher than the airplane.

Go Arounds

Restricted visibility makes a prompt decision even more necessary at night—be prepared in case the maneuver becomes necessary.

Night emergencies

Electrical emergency

The greatest electrical load is placed on the system at night, resulting in the greatest chance of failure. In case of a suspected problem, reduce the load as much as feasible. If you expect a total failure, land at the nearest airport immediately.

Engine emergency

Don’t panic

Establish a normal glide and turn toward an airport, or away from congested areas. Check to determine the cause and correct immediately if possible, using the engine restart checklist.

If unable to restart, maintain positive control of the airplane at all times, and orientation with the wind—do not land downwind. Check the landing lights and use them on landing if they work.

-

Announce the emergency on the frequency with ATC or UNICOM.

-

Don’t change frequency unless instructed to.

-

Consider an emergency landing area close to public access.

-

Use the before landing checklist, and touch down at the lowest possible airspeed.

-

After landing, turn off all switches and evacuate as quickly as possible.

Notes

-

Hearing improves at night—you start hearing things you haven’t heard before.

-

Know the nighttime definitions

-

Perpendicular red lights indicate a runway entrance

-

Two white lights on the wing as a tail position light

-

Pilot-controlled lighting—how many times do you click

-

Alternator/battery test—turn pitot heat on/off and notice amp rise to check alternator, turn off the alternator to check the battery.

Conclusion

Night operations present unique situations to a pilot and require diligence to maintain orientation and safety. Night flying is not inherently dangerous but it can require more effort. Overall, though, it is very enjoyable.

ACS Requirements

To determine that the applicant exhibits instructional knowledge of the elements of night operations by describing:

-

Factors related to night vision.

-

Disorientation and night optical illusions.

-

Proper adjustment of interior lights.

-

Importance of having a flashlight with a red lens.

-

Night preflight inspection.

-

Engine starting procedures, including use of position and anti-collision lights prior to start.

-

Taxiing and orientation on an airport.

-

Takeoff and climb-out.

-

In-flight orientation.

-

Importance of verifying the airplane’s attitude by reference to flight instruments.

-

Night emergencies procedures.

-

Traffic patterns.

-

Approaches and landings with and without landing lights.

-

Go-around.